As the tugboat, the Arkwright, charts its course along the Monongahela River, inside its tiny kitchen, the cook is the boss.

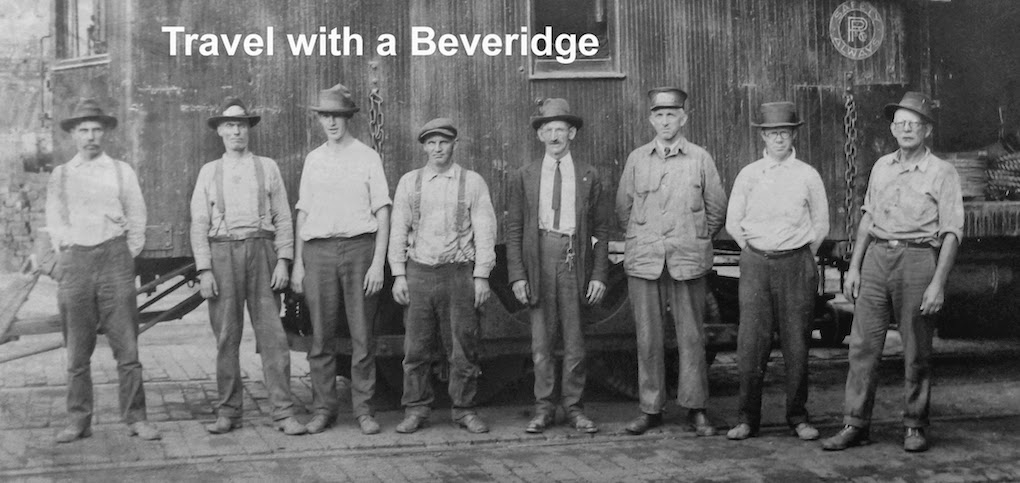

By Scott Beveridge

ALONG THE MONONGAHELA RIVER – The Arkwright's engine rumbled, sending short blasts of air to the tugboat's rudders, enough to steer it from shore.

The captain peered from the pilothouse, following orders to hook up with a dozen coal-filled jumbo barges and push them down river to supply a power plant.

While Capt. Don Lowe was at the helm of this 54-year-old tugboat, its seven-man crew was well aware that the women in the galley would call most of the shots while they would be on board for the next week.

"When they say the captain of the boat, they don't look at me," Lowe says earlier, while seated at the dinner table. He rolled his eyes and smiled at cook, Mary Husser, and stepped into the kitchen to follow her standing rule to rinse his dinnerware before retiring it in her stainless-steel sink. "You don't want to piss off the cook," said Lowe, 49, of Pittsburgh's North Side.

"They get told about washing your hands. Don't go into that refrigerator, into that ice cream without washing your hands," said Husser, 52, one of just 10 remaining female cooks who worked the tugboats that ply the

Monongahela River and move tons of coal, gravel, diesel fuel, fly ash and other products to market.

Competing towing companies have opted to pay deckhands a few more dollars a day to prepare their meals to cut shipping costs, said Capt. David J. Podurgiel, who coordinates boat traffic for

CONSOL Energy, which owns the Arkwright. That setup was bad for morale, Podurgiel said, and could lead to laziness and uncleanliness among boat crews without a woman to mother them.

Husser doesn't tolerate obscene language, cigarette smoke or co-workers who skip too many showers.

"If we're back in the galley, we try to keep our language clean," said Pat Snyder, 22, of South Park, who has yet to log enough hours on the river to master the job of roping and securing rusting steel barges.

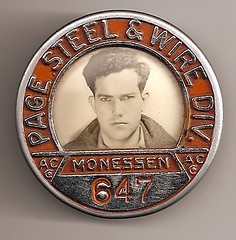

It takes muscle to work these boats - a role that is especially grueling during winter months - when most new guys quit because they can't take the bitter weather, said Russell Wiseman, 49, of nearby Monessen, Pa.,the lead man on the barges who helps the pilot guiding them along the water.

"You make it through the winter, you're good to go," said his deckmate, Kenny McDonald, 23, of Cheat Lake, W.Va. "If it's 20 degrees out there, it's 5 degrees out here. You get the wind blowing off the water..."

"These are a different breed of people out here," added Husser, of Millsboro. "I give them a lot of credit."

Husser was drawn to the Mon 15 years ago, when her two sons were in high school and old enough to fend for themselves while she's away from them, and her husband, Eric, every other week.

"It's hard enough for a guy to do this with little kids, let alone a woman," she said. "Working out here, you miss a lot."

"You miss a lot of kids' birthdays, weddings," added Wiseman, after the Arkwright left its moorings in Speers, moving north to Locks and Dam No. in Charleroi at a crawl of 4 mph.

Named after an old deep mine near Morgantown, W.Va., the Arkwright is pushing three barges, each of which is 195 feet long and brimming with 1,500 tons of coal. It will return to Speers to pick up three more loads of coal before embarking for Elizabeth. There are six more barges waiting there for the pass to Pleasants Power Station on the Ohio River in Eureka W.Va., a 406-mile round-trip that will last four days. It would require two, 100-car trains to move this amount coal, at a far greater cost.

And, this voyage required a grocery bill of $650 to feed the men who work rotating six-hour shifts between six-hour rests on cots in tiny rooms whose walls vibrate around-the-clock with the steady hum of the engine. They earn between $9 an hour and $12.43 an hour, depending on their seniority, for an 84-hour work week. Their living room is just big enough for a few chairs, a television with a 12-inch screen and built-in videocassette player mounted in one paneled wall.

"It's small," said Husser, whose quarters are just beyond the first door from the stern. "It's the size of a cell, really," she said, unpacking a suitcase carrying her essentials, which include DVDs and paperback books. She has a private bathroom, one smaller than a bedroom closet found in most houses on land.

In the galley, her three refrigerators facing the starboard are freshly stocked with 12 pounds of ground beef, 11 pounds of chicken, six pounds of Delmonico steak, nine heads of lettuce, 15 dozen eggs and three pounds of butter. Forty pounds of potatoes and six pounds of onions are brought on ship, too, for the journey.

"If someone gets up from my table hungry, it's their problem," Husser said. "I make my own bread, buns and cinnamon rolls. I make a to-die-for peanut butter pie," she said, announcing to the crew that this dessert will be on the next day's menu.

"Christmas comes early," said pilot Vince Dentino, 27, of nearby California Borough, reaching for a sample of the first day's menu, which always includes hot dogs,

kielbasa and chili prepared by the relief cook.

She's quick to say that this job is no holiday. Once, 18 inches of water rushed into her bedroom in a wake caused by the tugboat, when it suddenly moved faster than its haul, causing it to dip under the barges. "Shoes were floating around," Husser said.

Her worst scare came when her boat "got caught in the rolls," or choppy water below Point Marion Locks and Dam, while the vessel was moving a derrick barge, one designed for crane or drilling work. "The oldest deckhand panicked," she said, before the pilot regained control of the boat.

Other times, Husser finds herself mediating arguments between deckhands whose patience has been tested by spending too much time together in close quarters.

"Donny and I are like the psychotherapists on the boat," she said. "The captain and the cook become the mother and father of the boat. Just think if you are stuck in the house with the family for seven days. It takes some getting use to."

On this day, the cruise downriver is delayed about an hour while mechanics made repairs to the massive, spit-shined engine, which filled the boat's hull. Another half-hour is lost while the Arkwright detours from its route to rescue the stalled Jacob G. and tows that tugboat, owned by Mon River Towing Inc., back to shore in Speers.

Wiseman and McDonald finally secure three coal-filled barges to the bow of the Arkwright before it chugged toward the aging and crumbling Charleroi locks, which have been scheduled for replacement over the next decade by the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The barges were lassoed to the lock wall, its front and rear gates swung shut, and gravity lowered the water 16 feet to match the river level in the pool below the dam. The front lock gates opened and a whistle sounded, alerting the pilot that the Arkwright could continue its long journey.

Husser's day would end at 7:30 p.m., after the sun had set and it no longer cast long shadows across the river that rolled with a blanket of new-fallen, yellow leaves. She planned to return the next day to the galley at 4 a.m. to begin breakfast. It's her favorite time of day, she said, when the moon reflected on the near-still current, making it look as if it were a sheet of black glass.

Published with permission of the

Observer-Reporter

PITTSBURGH, Pa. – The delicate blend of flavors that gives Thai food its appeal can be found in the country’s most-popular brand of beer.

PITTSBURGH, Pa. – The delicate blend of flavors that gives Thai food its appeal can be found in the country’s most-popular brand of beer.

These tours last about eight hours, and they include talks by naturalists, who point out black bear munching on grass along cliffs, or harbor seals resting on floating icebergs.

These tours last about eight hours, and they include talks by naturalists, who point out black bear munching on grass along cliffs, or harbor seals resting on floating icebergs.